On the grand historical scale, until quite recently Great Britain was the number one world superpower. An Empire build over centuries which at his height in the 1920s covered a quarter of the world had brought immense wealth and status to Britain.

Yet just a few decades after its peak decline took hold, largely due to the huge financial impact of two world wars. By the 1960s, Britain had become known as the “sick man” of Europe and looked to membership of the Common Market (which evolved into the European Union) to shore up and survive in the new economic world order.

Then entered onto the world stage a certain Margaret Thatcher in the late 1970s. Mrs Thatcher, also known as the Iron Lady due to her uncompromising style as Prime Minister, forced the UK to rise like a phoenix and in just over a decade set it on a path to being the world’s fifth-largest economy today and home to one of its most advanced technology and innovation sectors.

So, how did the Iron Lady achieve so much in such a short space of time? Well, there are of course a range of factors to weigh, but I believe the answer can in large part be boiled down to three words: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

Converting the “Crown Jewels”

Mrs Thatcher is a divisive figure and her detractors say that she “sold the Crown Jewels”, a rather emotive way to describe her privatisation of a range of previously state-owned assets and sectors. Her actions were certainly radical, covering everything from power stations and steel to airports and telecomms. But they were necessary and reinvigorated the country as few could have dreamt. Indeed, her champions would contend that she averted complete economic collapse and restored the “Great” in Great Britain.

These “jewels” benefitted hugely from privatisation and the profit imperative. New owners committed to cutting-edge industrial technology, efficiency and modern ways of working, shaking off a sclerotic past where management was so often old, tired and lacking in motivation to modernise, not to mention funds.

Ordinary people benefitted massively too. The Initial Public Offerings through which assets were privatised very often included the public if they were clients of the selling entities, not to mention all the institutional pension fund money that flowed in. Now directly answerable to shareholders, these newly minted Public Limited Companies flourished, as did the whole economy as empowerment flowed through.

Heading off danger

Of course, there are justifiable concerns around the privatisation of such important industries and services. The British Government ensured control by installing independent and in some cases governmental bodies whose role was to act as watchdogs and monitor behaviour, monopolisation and competitive fairness.

Alongside public opinion, shareholder influence has also played an important role in ensuring the responsible behaviour of large companies. Today, you will find that most have signed up to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) principles, and in fact, many are leading the way in doing good for society and the environment, as well as doing well financially for their stakeholders.

Learning from Britain’s journey

My observation as a resident in Vietnam for several years is that the Vietnamese miracle has the potential to put the British economic revival in the shade.

Despite suffering through almost 1,000 years of foreign domination, Vietnam has survived as a national culture with its own distinctive language and identity. Today Vietnam has become one of the fastest-growing economies in the world thanks to its spirit and leadership. However, I believe that she is at a tipping point in her history in terms of economic development.

Just as FDI was the lifeblood of the British economic revival, so it has helped propel Vietnam into the dynamic economy it has become. Yet Vietnam is still not recognised as an emerging market. In the eyes of international investors, moving to the next stage of economic growth and shaking off the “frontier market” label means a lot.

How does Vietnam power up?

Were Vietnam continue on its current trajectory, it would no doubt still see robust growth. But to make a truly transformational leap forward, Vietnam needs to be brave and open up her economy further still to the rest of the world. If Great Britain had not made its great leap in the 1970s and 1980s, it likely would not merit the name. The choice is just as stark if Vietnam’s phenomenal growth is to continue rather than stall.

As a career financial and business advisor, to me, the way forward seems clear.

First up would be increasing the levels of accepted FDI, particularly in the financial services sector, and offering investors more surety over the future. I have seen countless instances where FDI could have flowed into domestic institutions, only for the potential buyers to be put off by investment limits and a lack of clarity about Government plans.

Second and relatedly would be a reconsideration of state “silverware” and a broader conception of what the best method of Government retaining some control could mean. It certainly doesn’t have to be a controlling stake when other methods of oversight can function so well.

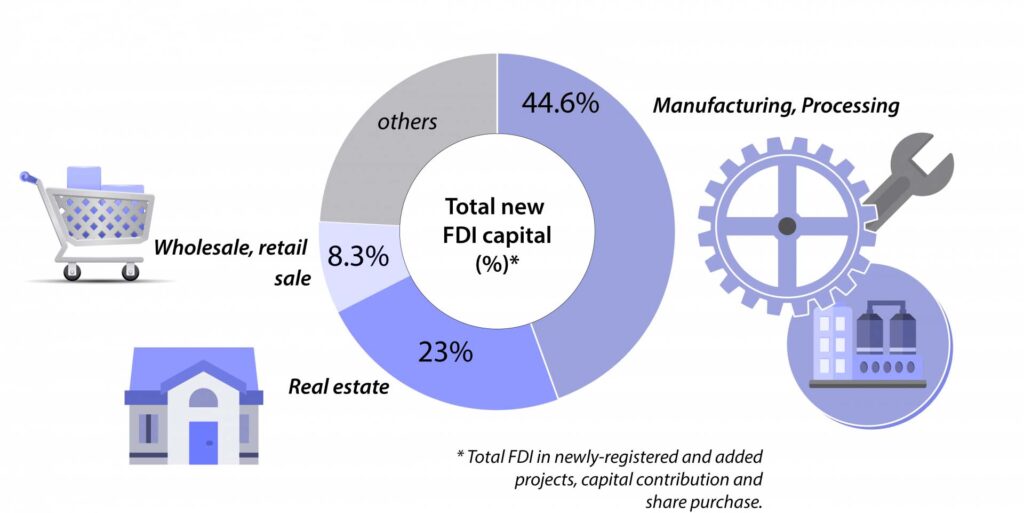

But third and most important is recognising just how big the wall of money waiting to flow in is. Manufacturing gets the most attention, but real estate, food, construction, mining, education, IT and more are all attracting many millions, if not billions, of dollars a year. Just think what kind of growth could be unleashed if more of international investors’ hopes for their projects could be met, and their residual fears allayed.

All that remains is for a few more barriers to come down and Vietnam’s economic miracle can truly become one for the ages – and just at the time when others both near and far seem unfortunately to be going into decline. In short, the stage is set. I cannot wait to see my adopted country take its rightful place as a global player and commence its second act.

Read more at vietnamnews.vn